|

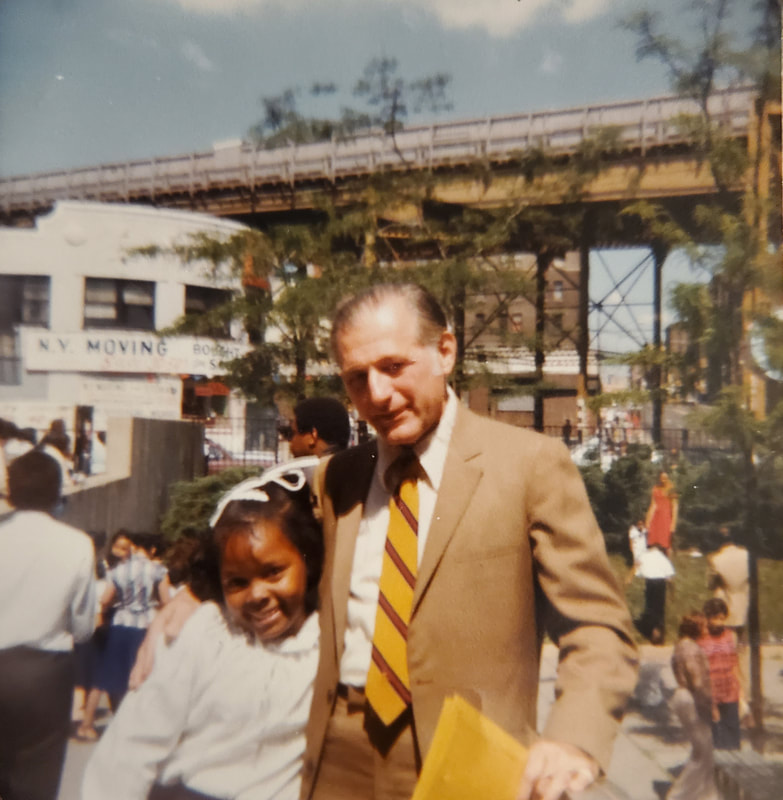

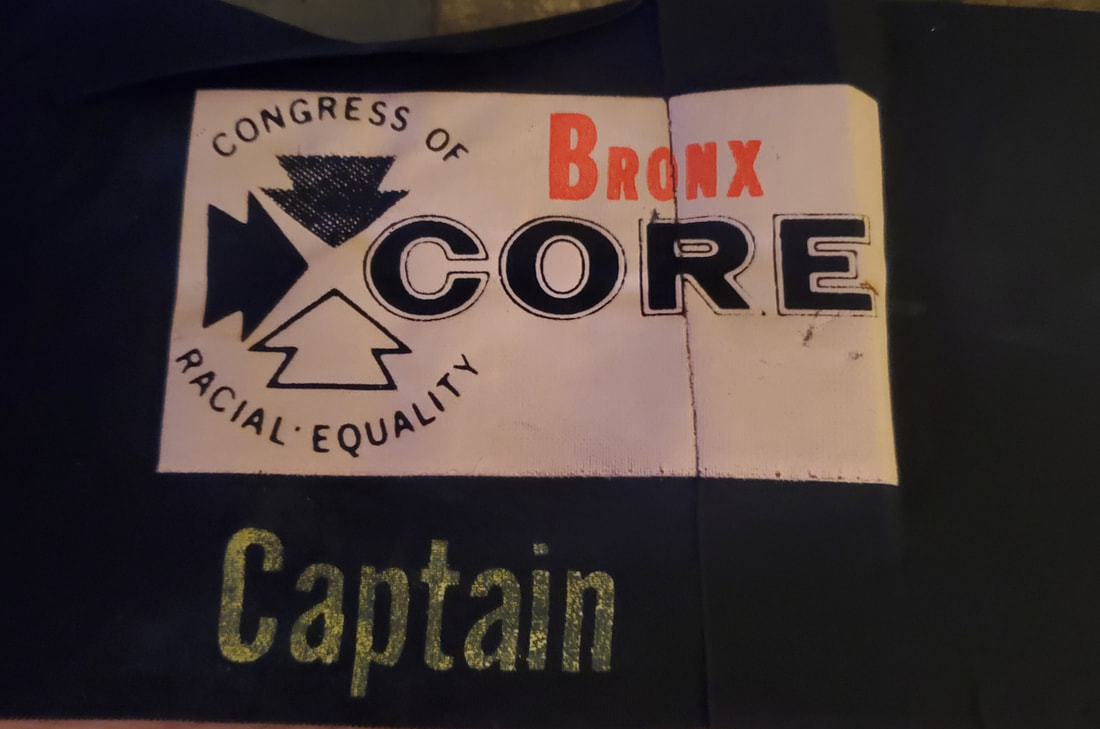

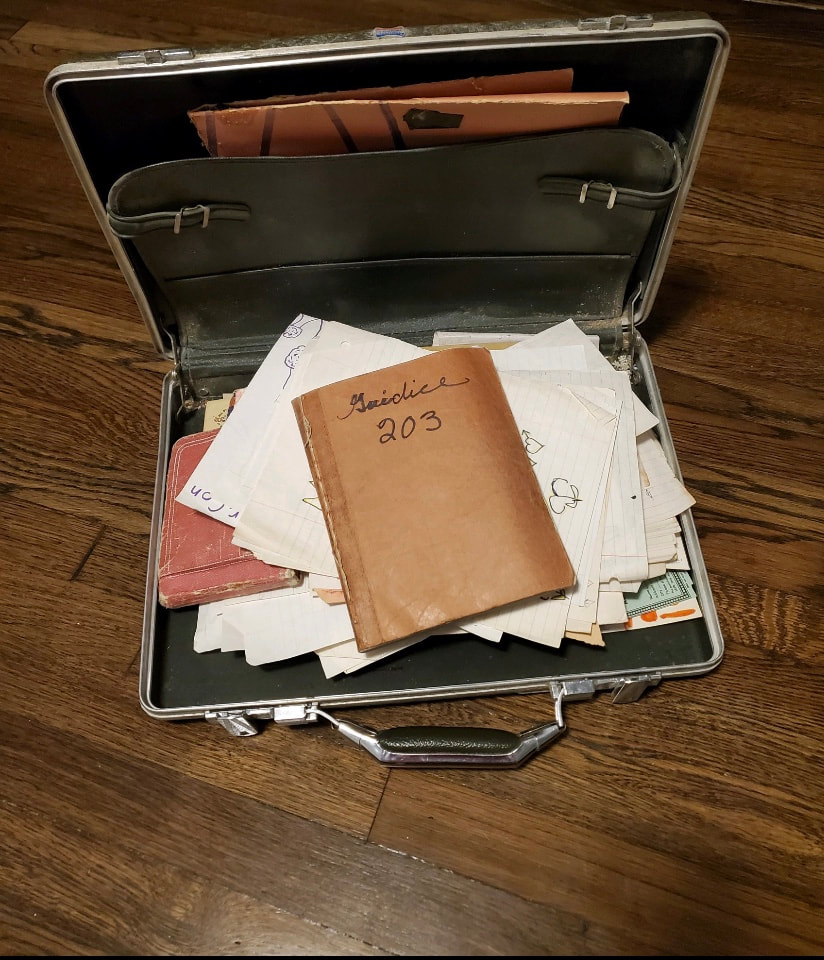

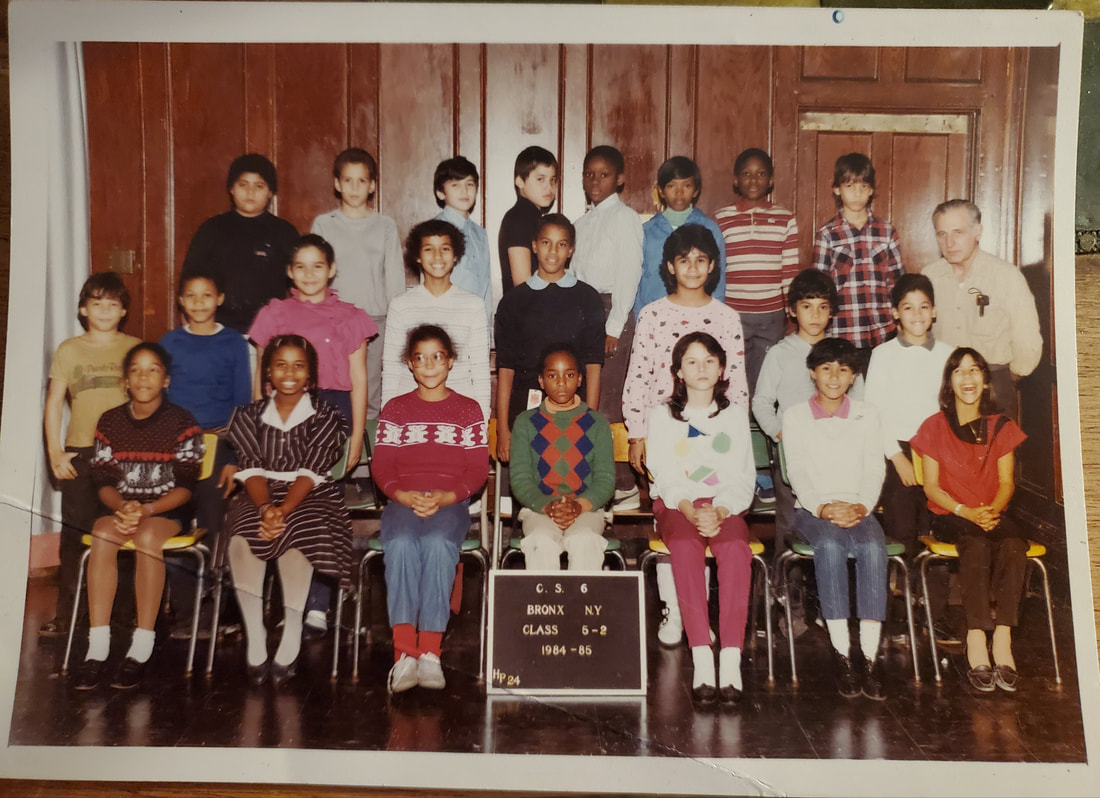

I happened to be traveling through Galveston, Texas on June 19th two years ago. I went into a store to buy some Texas BBQ spice rub and the black female owner of the establishment had hung a large sign in celebration of Juneteenth. In an effort to get to know the people of Texas, I asked the storeowner about Juneteenth, as I had never heard of it. This woman explained to me that Juneteenth honors the day when enslaved people in the State of Texas were set free. “The Emancipation Proclamation had happened two years earlier, but Texas didn’t have a lot of Union soldiers around to uphold the new laws,” she explained. “Texas was late to the party, until June 19th, 1865, when a Northerner read federal orders for black Texans to be set free from slavery.” I was completely humiliated by my ignorance of this historic event. Juneteenth is now gaining the recognition that this day has deserved since it was declared by the State of Texas in 1980. Why, like the State of Texas had been after the Civil War, had I been so late to the party in learning what this day was all about? The following story is about a man who wasn’t from Texas, nor was he black. His name was Domenick and he lived in East Harlem, New York. But I believe that the woman selling me BBQ spice rub would have seen him as kin. Perhaps we will all see Domenick as kin after hearing his life’s story. Domenick Guidice was born in 1920 to parents who had immigrated to the United States from Naples, Italy. At age 18, he was drafted to the United States Army during World War II, but served as a typist within the States, which suited him well. After all, Domenick wasn’t one to fight; he was a lover of words and a poet who scrawled words on every napkin of each diner he frequented through his teenaged and young adult years. After the war, Domenick went to college and became an accountant. He worked for MGM Studios in New York City and made good money. But something else was happening during those years. The Civil Rights Movement had begun to unfurl, and Domenick started attending underground meetings to fight for racial justice. Domenick realized that being an accountant held little meaning for him. When the MGM office for which he worked relocated to California, Domenick declined to go. Instead, he began attending protests for Civil Rights in New York City. And by the year of 1963, he became a Captain Leader for the March on Washington. That was on August 28th of that year. Just two weeks thereafter, on September 15th, four black schoolgirls were killed in a bombing with sticks of dynamite at a church in Birmingham, Alabama. Domenick got in his car and drove from New York to Alabama to protest again. It was during this year when he met the love of his life, Joan Ferguson. Joan had been an actress in Greenwich Village. She watched a white American man being arrested with a few local priests during a rally for Civil Rights on the television. Joan joined the picket line after witnessing the quiet fury behind Domenick’s countenance as he was being hand-cuffed by New York City police officers. She married him less than one year later. Domenick and Joan had two children. They moved to the South Bronx, and Domenick went back to college at the Long Island University to get a second degree. This college experience was far more in keeping with his personality, and Domenick secured his first teaching job educating 5th graders in the Castle Hill Section of the South Bronx. It was there that he instilled his love of poetry and reading to children of all races. Domenick brought a briefcase to work each day; because of his savoir faire with language, he referred to this briefcase as his “valise”. Within the valise, Domenick kept letters from his 5th grade students. These were the letters that were written towards the end of the schoolyear, which, as any teacher knows, are typically both flattering and apologetic in nature. Because I know Domenick’s daughter, I was able to go through his valise just last week. Amongst the many writings therein were two letters from the principal of his elementary school which thanked him for organizing assemblies to educate the students on the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Even though Domenick was now a teacher and a father, he refused to stop fighting for racial equality. From his initial beginnings of working as an accountant for MGM, to his years of protesting publicly for Civil Rights, Domenick had redirected his life’s work towards teaching children. Because the pay for a schoolteacher was not nearly as good as what an accountant would earn, Domenick drove a taxicab each night to make ends meet for his wife and children. Domenick’s life path was one that was imbued with great meaning, but it was not without personal sacrifice and anxiety. He kept a leather-bound book within his valise where he wrote his poetic musings. One can picture him with a furrowed brow in the teacher’s lunchroom in the 1980’s, scribbling his thoughts, concerns and worries about the future that the world held for his students. Amongst the many penciled scrawls in his leather-bound book, Dominick wrote this: “Humanity can be blessed many times over and also be incomprehensible. The long history of torture and degradation of the weak and innocent is yet to be eradicated by us. Many tears have been shed by the innocent and brave.” Towards the end of his teaching career, Domenick developed early dementia. Very few noticed his forgetfulness and difficulty finding words, except for the black female principal at the Community School 6. Her name was Eloise and she was concerned for this teacher, who had only two years left before he could retire with a full pension. Eloise loved Domenick and knew that she needed to protect that pension for which he had worked tirelessly in helping children learn to read. So, she took Domenick out of the classroom, kept his status as a full-time teacher and created a position where he could assist other teachers in reading activities in the school. (Perhaps this was what Domenick had marched for all along; equality in work for all people, and the overriding belief that people could care for each other with justice and compassion. If only they dared to try). Going back to the modern-day tale of my ignorance of Juneteenth, I am struck by many things about Dominick’s life. While the March on Washington was incredibly bold and daring, as was his trip to Birmingham Alabama two weeks later, it was Domenick’s day-to-day work which made him a true leader in the fight for racial equality. It makes one ponder and imagine, what if more people had done this in 1963? Even if they didn’t attend these large and famous protests, what if people took a personal stance on ending racism as they lived and raised children and performed the most mundane of tasks? Where would we now be as a society if there had been more Domenicks who cared about every child, every person, no matter the color of their skin, and who wanted to stop the tears “shed by the innocent and brave”?

It goes without saying that we wouldn’t be where we find ourselves today. As the world will finally celebrate with reverence a holiday as potent as Juneteenth on this very week, may we all learn from Domenick. May we be very careful about what letters, stories and ideas we carry within our ‘valises’ and bring forth to the world. May we remember that it needn’t be a holiday to carry out racial justice in all that we do. Domenick grappled with fear for the future, but what if our actions now would have eased that fear? What if we challenged ourselves about the nature of racial divide and did something every day to narrow the distance between each other? In Domenick’s own words, “Humanity can be blessed many times over.” Let us celebrate Juneteenth with the soul of Domenick Guidice and the souls of the many people who suffered without reason from racial inequality. And let’s not stop on June 20th, either. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|