|

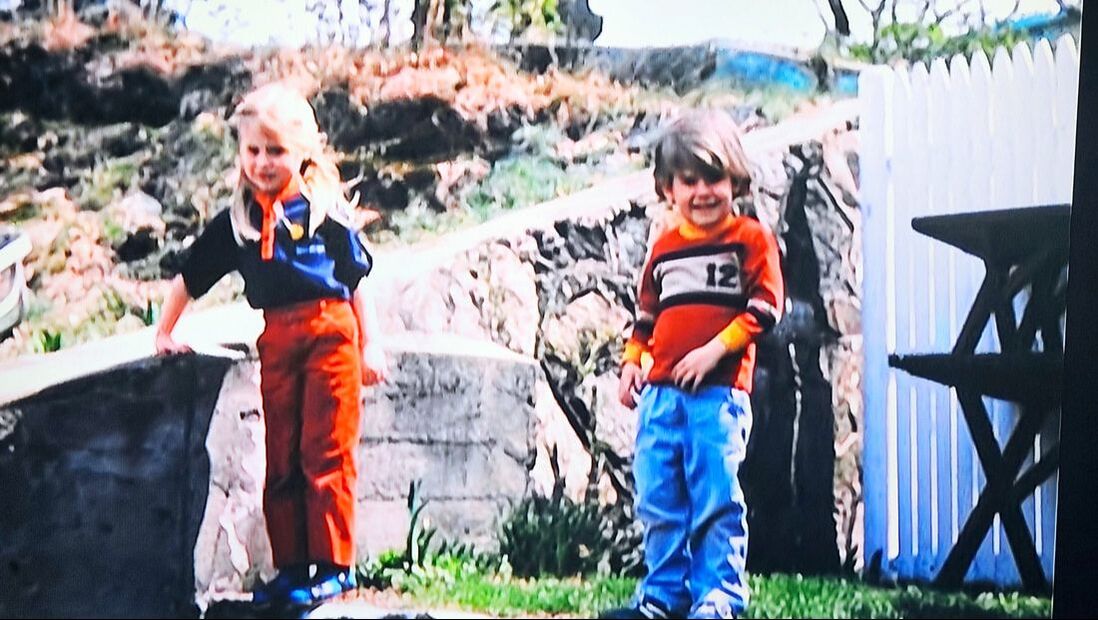

My brother Ben was born almost exactly two years after me and this was his very first sentence as a toddler. You see, Ben and I had a very close relationship. And we instantly connected as children via our mutual love of wrestling. Yes, we fought and tumbled in the most wonderful of ways as children. Our parents had an old station wagon, the kind with the third backseat which faces the bumper of the car. Our Mom often said when she glanced through the rearview mirror that she saw the flailing limbs of Ben and I and she knew we were fine. She called us her Bear Cubs; we loved our title and lived up to it. Years later, Ben hit puberty and he grew to be over six feet tall. We stopped wrestling then, because my days of winning were over due to Ben’s increasing physical size. But that didn’t stop our closeness, and we replaced teasing words and humor for the wrangling. We got each other through middle school and high school, our connection growing only closer as we grew closer to being full humans (adults). In my twenties, I had gone to college, secured a job and got my first studio apartment in Brooklyn, New York. I thought I had done everything right in my life; but I felt depressed and sad much of the time. Ben came to visit me in that studio apartment and fell in love with New York. “Becca, your life is great! I would do anything to have what you have right now.” Only I didn’t feel the same way about how things were going. I longed to move to another state, South Carolina or Arizona and begin a new adventure, but all of my family was in the Northeast and I was too afraid to leave them. “I don’t understand your fear of leaving us,” Ben told me. Ben wasn’t afraid, so he got a job as an entertainer on a cruise ship that traveled throughout the Caribbean. He had dropped out of college (much to our mother’s dismay) and was fearless in his quest for adventure and taking risks. I didn’t understand why I had followed an established career path and felt so despondent. My depression became more difficult to manage, so I started on some anti-depressant medication and went to therapy. Ben would call or visit from his cruise ship life and he was puzzled by my sadness. While he approved of me finding a therapist, he hated that I was on medication for depression. “Those pills you are taking are garbage. I wish you would stop, because that shit is no better than street drugs.” Hmmmmm. This was the first major disagreement we’d ever had. I knew I needed the medication and it was helping me. I also sensed a major depression within Ben. Of course he couldn’t see it and was living his best life on a cruise ship, dating young women and sailing between islands. I knew there was nothing I could do to change his mind about psych medication and I also knew that there was no one like Ben to pull me out of the despair I felt. He often yanked me out of my apartment to go dancing or have a beer when I wanted to be alone. I needed his belief in me. He saw me as a success, a bright light that he refused to allow to be shut out from the world. That is what a best friend does. And it helped. I eventually moved out of that studio apartment and started to live. We got older and hit our thirties. Ben had left the cruise ship industry and was working in Manhattan as a bartender. He began to study to become an airline pilot. I was so proud of him; he had lived his life out of sequence, he partied while being young and then settled down when he matured and this path was working for him. Until one day, it wasn’t. When Ben was 35 and I was 37, the depression that I had known was lurking within him came out to play. And it wasn’t the joyous playtime we had known as children. No, this was the particular brand of depression which took everything from Ben. Including his friendship with me. My depression always resembled that of an old woman in a housecoat, mulling over her poor life choices and standing by the window with regret during autumn, as leaves fell from trees. In contrast, Ben’s depression was one of fury. He became so angry with the world that he lashed out at everyone, could no longer keep a job, and then shut out our family completely. The young boy of antics and laughter had disappeared, and in his place stood a tall, raging monster who refused to engage in meaningful conversation. I was lost. I didn’t know how to get through to him, so I chose to use his same tactic to fight back. I sharpened by weapons, I matched my anger with his. The result was a full on war between the two of us. We existed on one lone field, my troops in tents facing his. Sometimes we riled our troops and they fought with such bloodshed that it was disgusting to behold. Other times, we silenced our troops and they stared angrily at each other across that field with nothing by silent rancor. This war lasted for almost a decade. The nasty and violent fighting was reserved for the beginning and middle of the war, while the bitter and frosty resentment reverberated towards the end. It was January of 2023 when I got the call that Ben had died. As any general would know, it was time to send my troops home and fold up the tents in which they had faithfully slept while waging my war against Ben.  At least the war was over, I thought. There are some perks to the end of a war. Neighborhoods gather to plant crops, masons lay bricks for the foundations of homes, entire cities are rebuilt, sometimes with more luster than ever before, and unity reigns over division once more. Except I had none of this rebirth to lavish within because the war between Ben and I had no resolution. No winner. No white flag. Like most wars, it was futile and stupid and mean-spirited with no end result. I met a woman several years back, and she was in her nineties then. So, she was old. She told me that her parents were living near Times Square on the day that World War II ended. Known as V-E Day, this woman was a witness to the end of a very long and tumultuous war. “People walked in the streets and hugged each other! Perfect strangers! My father invited people over to share dinner with us and we didn’t even have enough food for ourselves! But nobody cared. The war was over!” The old woman exclaimed. Now that is what the end of a war should resemble, right? And then I remembered something else about this incredibly old woman. She was able to describe an event that had happened in childhood with exact precision (the end of a major war), and yet she couldn’t remember anything short term, like eating egg salad only two hours earlier. This is actually a common finding in people with dementia: their long term memory stores of childhood remain intact, yet their short term recall of events of the previous twenty four hours is irretrievable. That is how I figured out how to end the war, for both Ben and me. I looked back upon the years we spent fighting, and I told myself to stop. I replayed our hideous exchange of words and I forced my brain to stop. I am learning from this old woman and people with dementia that the recent history may not be as important as we think. It is the old, old memories that make life burst into bloom. I decided that the last decade at war with Ben is to be forgotten and that it is our task for me and Ben to relish in the extraordinary kinship that we had years ago. Our birthdays are coming up this week. They are four days apart and we used to celebrate together. This will be our first post-war birthday. I am looking forward to rough housing and mischief, laughter and limbs tumbling across the living room floor. I’m sure that Ben will tune up his guitar and we will sing together. These are the old, old memories where we are reminded that what was once divided, is now at last united. We will always be the Bear Cubs, as evidenced by Ben’s first full sentence, “Becca hit me.”

0 Comments

“No Day Shall Erase You From the Memory of Time” This quote by the poet Virgil is displayed upon the entry of the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York City. It is an arresting thing to see, should you ever find yourself in Manhattan. It also reminds me of a story surrounding the passing of the mother of my good friend Janine. Janine is a registered nurse, and an excellent one at that. She is skilled at making split second decisions for her patients, which often requires that she checks her emotions at the door when she arrives at work each morning. Good healthcare workers are known for this separation of personal attachment from people they are treating, especially in an emergency. It is for this reason that it typically isn’t advisable for nurses and doctors to treat family members. Because emotions will always obscure our interactions with loved ones.

At this time, Annette developed significant trouble with her breathing. Janine was concerned for her mother, and often went and stayed overnight in the hospital rooms where her mother wound up. But as soon as Annette’s health worsened, she would rally and go back home to host Rummikub parties for her girlfriends. There was a spark within her that refused to be put out. It wasn’t until Easter of the following year and Annette was in the hospital again, when a nurse pulled her daughter Janine into the hallway to talk. “It is really time to consider hospice for your Mom. At this rate, she will likely die within a week, but it won’t be comfortable and she will be gasping for air.” Janine was torn. The nurse within her knew that hospice was the best idea. But the daughter within feared losing her mother. Janine returned to her mother’s hospital bed and brought up the idea of hospice. Annette’s reply tore at Janine’s own ribcage: “Are you saying that you just want to erase me?” I know Janine pretty well and she is a very quick thinker on her feet. “It isn’t that I want to erase you, Mom. But I think it would be a good experience for you to try hospice. If you don’t like the place, you can always leave.”

Janine and Dr. Buttles had a huddle between themselves. They were both on the same page. They wanted Annette to feel calm and at peace and they wanted the process to go quickly. “May I spend some time talking to your mother?” The good doctor asked Janine. Janine agreed and went out for Italian food with her husband at a local restaurant.

Dr. Buttles spent two hours talking to his patient Annette. At the end of the two hours, several things were accomplished. First, Dr. Buttles discovered every single detail of Annette’s life, including why she named her daughter Janine (it was because she loved flying to Paris and adored French culture). Second, Annette made it abundantly clear to Dr. Buttles and the priest on staff at this hospice place that she didn’t want others to pray or engage in any religious practices for her benefit. And thirdly, Dr. Buttles was so persuasive and kind that Annette agreed fully to hospice and even stated, “If we are going to do this, let’s DO THIS! Let’s get started!” Janine returned from dinner with her husband to find a very relaxed mother. After all, Dr. Buttles knew what he was doing: he gave his patient morphine pills frequently to gently slow her breathing and Annette opened her mouth readily for this medication. She no longer gasped for air, either. As the night wore on, Janine and her husband and several family friends knew they had to go home and get some rest. Janine was exhausted, as the hospice decision and transfer had occurred during the past 24 hours. As she sat at the edge of her mother’s bed, Janine asked her mother if there was anything that she could do for her before leaving for the night. “Yes, you can do something for me,” Annette replied, her countenance tranquil and sublime. “I want you to go home and fv#k your husband.” The daughter within Janine was appalled. Annette had never used the F word as a verb, and certainly not to her daughter in a room full of family and friends! But shortly after the initial shock, the nurse within Janine remembered the awesome power of morphine. Janine knew better than anyone what this drug was capable of. For end of life matters and to suppress breathing, morphine is the drug par excellence. It can also loosen lips, as it did in this case. Janine awoke the next morning and made pastina to bring to the hospice house for her Mom. Yet she got a phone call from a worker there who said, “Your Mom isn’t waking up.” Janine arrived and her mother was peacefully sleeping. Still alive, but unable to open her eyes and converse. A throng of family and friends were within the room, enveloping Annette with their love and support. Janine had a family member who was a monsignor of the Catholic church. He suggested performing Last Rites, so the group gathered in a circle while the monsignor read aloud what is called the Commendation of the Dying. In the middle of this officiation, a black crow flew into the window above Annette’s hospital bed and fell to the ground. It was at this moment that the crowd realized they had violated Annette’s request that no religion be offered to send her on her way. “That crow made a very loud thud and it scared us a little,” Janine told me. “We stopped praying at that point. But that crow eventually got up and flew away a few hours later. Just as my mother finally stopped breathing for good.” As ‘end of life’ stories go, the story of Annette tops the list as one of my personal favorites. I have never met Annette, but in listening to Janine and writing this, I feel almost certain that I have. It all goes back to that quote by Virgil: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” Annette had feared the idea of hospice and asked her daughter if she would be erased. From her young beginnings of sunbathing and flying across the Atlantic Ocean, to raising her daughter who would become a nurse, to riding on her “yacht”, Annette had a wonderful life of parties and joy. And her departure from this world was equally as dramatic as her life had been, when she instructed Janine to “go home and fv#k your husband”, after which a black crow flew into a window to put the kibosh on the monsignor’s prayers. This is a working theory which suggests that Annette was not erased after all. None of us are. That dude Virgil was onto something. We are not erased from the world on the day that we leave it. We matter. The next time I go boating, I will look out on the shimmering water for a woman on a pontoon with a broad smile and an open laugh. She will appear in streaks of brilliant color, just on the periphery of my vision. Never to be erased.  I am a pelvic floor physical therapist who works in Assisted Living Facilities in Florida. I used to treat men on an outpatient basis for prostate cancer. I loved that job, but something tugged at me to help people at another stage in life. I wanted to work with those who couldn't get to such a setting; I wanted to bring a unique perspective to those who might not be able to go out into the community as readily as their younger counterparts. I treated a man today who is 95 years old. I looked in his medical chart and saw that he'd had his prostate removed due to cancer about five years ago. I entered his room and asked him what had brought him to the place where I was working. "I lost my darling two years ago," he told me. "My wife died and she was my everything." My heart dropped into my pelvis. My brother died several weeks ago, so I knew something about loss. But I still have my husband. I asked more of my patient. He had been leaking urine ever since his wife died. But he hadn't suffered full-on incontinence until now. This made me think. I walked with my patient to the bathroom and asked him to sit on the toilet. He needed help lowering his pull-ups and shorts. Yet as he sat there and we spoke of the long, dull and awful stuff of grief, I heard a stream of urine. It was a full stream, a stream which I believe released his bladder completely. When he was finished, and his shorts were up, we walked to the Dining Hall. This patient seemed different during our walk. This man stood taller, he spoke with more vigor, and we laughed and met other people along the way. I encouraged this man to sit with two other men who live at the Assisted Living Facility for lunch. One had been in Alcoholics Anonymous for 35 years. Another man I am treating for urinary incontinence due to bladder cancer. They embraced my new patient with the kind of masculine energy that makes me smile. I sat with these three men as they acclimated themselves to eachother. All of them are in their eighties or older. All of them have suffered loss of some kind. And yet they know the secret to survival that is lost to many people. They know shame. They know the depravity of age. They know what it is to relinquish all that they once were as people. But they know the peace that accompanies all of such things. Cancer, age, and addiction is something that will find all of us. But the victory of sitting at lunch with fellow comrades? There is no way to gauge the price on that. I know this now. Because I have sat with these men. And they know the kind of strength that will stay with me until I am in an Assisted Living Facility and need some people to sit with. I am sure I will find my people because I have already met them. Forty years from now, if we have the great fortune to be alive, we will sit together. We might have trouble using a fork to bring meat to our mouths. We may leak urine. None of these small details will matter. What matters is that we will be together. |

Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|