|

I met the great Katrina Rolnik while pushing a wheelchair into her grandfather’s room at the nursing home. My patient Henry was sleeping, but his grand-daughter arose from her seated perch at the foot of his bed. She was diminutive and just under five feet tall. Yet her personality was anything but small. Katrina introduced herself and shook my hand. Her two younger brothers were there, and she commanded, “Get off your cell phones. Grandpa’s physical therapist is here to speak with us.” I explained to Katrina and her disinterested brothers about their grandfather’s rehabilitation plan. We will give him lots of therapy, I promised. Several hours a day. He may not like so much activity, I said. Most people over ninety do not enjoy being pushed to move. “That is not my Grandpa,” Katrina told me. “He used to get on a bus to Atlantic City to gamble once a week. He was very active until two weeks ago. That is when they diagnosed him with leukemia. But I know he can get better.” At this declaration, Katrina’s grandfather Henry opened his eyes. “There she is, Katrina,” Henry said. “That Blondie. She keeps disappearing on me. She comes in my room and then flies away like a bird.” I was embarrassed to concede that this old man’s assessment of me was correct. Earlier that day, I had reviewed his medical chart, gone in to introduce myself to him, and then abruptly left to assemble a suitable wheelchair for my patient. It had taken an hour to do this, as the leg rests, cushions and various sizes of the wheelchairs in this nursing home were kept in a jumbled mess in the basement of the building. I had finally been victorious in my quest, so before I went to lunch, I popped in to tell Henry that I did have a wheelchair for him and would be bringing it to his room in the afternoon. Meeting Henry’s grandchildren had been my third visit to his room in one short day.

Henry was doing splendidly in rehab. Until the day that he wasn’t. Katrina had taken that afternoon off from her waitressing job. She was working to pay her way through college. Yet Katrina was always in the nursing home. As a woman in her early twenties, I found this to be unusual, as was her admonishment of her brothers to get off of their cell phones to listen to a healthcare professional. This was not representative of my opinion of millennials. On the afternoon when Henry was no longer his usual self, he turned to me and said, “No exercise today. I do not want to do this anymore.” I pushed Henry into the garden adjacent to the rehab gym. Katrina followed, her tiny legs keeping up with my strides. The sun was magnificent that day. Morning glories bloomed on a trellis. Henry squinted, so I stood in front of him to shield his eyes with my shadow. Katrina looked at me quizzically. She was alarmed. The three of us sat in the quiet of the solar beams which enveloped us in our confusion. I knew exactly what was happening. Henry was ready to die. A few days later, I walked past Henry’s room. There sat Katrina, in her constant vigil. She was weeping. I walked into the room and saw Henry’s chest rise and fall rapidly, his mouth gasping for air, like a guppy. Katrina’s beautiful Polish nose was red. “He is disappearing, Blondie. Only he won’t come back, like you did with the wheelchair. He is leaving me forever.” I had witnessed death several times in this line of work, but I did not know how to help Katrina in that awful moment. Katrina stayed for the next several days, she slept upright in a chair and only went home to shower. It was early one morning when Katrina was gone that Henry slipped away. When it comes to dying, there are only two kinds of people in this world. The first kind waits until their favorite nephew flies in from Knoxville, Tennessee before they take their last breath. The second kind of person waits until no one is left in the room. Henry was this kind of person. He did not want his grand-daughter Katrina to carry the image of his death with her. I read Henry’s obituary. He was buried in a plot with his wife. She had died over forty years ago of uterine cancer. Henry had summoned such strength through not only war, but the loss of his true love. Having known him only a short while, however, none of this surprised me. There are some people who can survive as a Polish Jew under Nazi rule and are determined to live in the particular kind of grace that he had chosen. Almost one year after Henry’s passing, I ran into Katrina at a restaurant where she was a waitress. I was sitting down in a chair and Katrina was standing while taking my order. She seemed so much taller than I remembered. So much older.

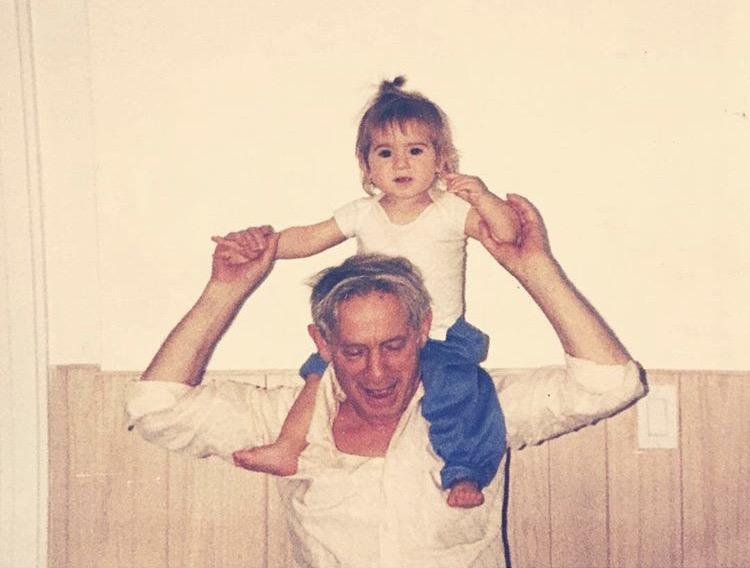

I often wonder of the mark that we leave behind in this world. The indelible essence of who we are and who we become throughout life. I really have no doubt that we do leave our fingerprints here as I remember the completion on Henry’s face, when he looked at Katrina before he died and sighed with unbelievable happiness, “I still remember the day you were born.”

|

Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|