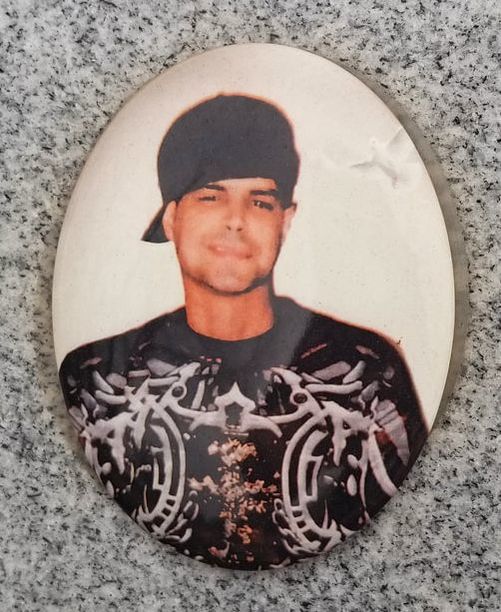

David was handsome by anyone’s standards. He had a strong jaw, a prominent brow and hairline, a broad-shouldered and muscular body. Had I met him as someone who was not in the healthcare profession, I might not have noticed that he covered his mouth when he talked. This was because the radiation given to his face had caused some of his teeth to fall out. David was losing weight when he was admitted to the nursing home, in part because he could not swallow enough food to nourish his body. He needed some physical therapy to strengthen his limbs. It was during that time that I got to know David. Women from his church visited David to pray with him. He had a very strong belief in God. He declined the use of antidepressants to help to boost his spirits. In fact, David had already signed a DNR (Do Not Resuscitate order), which meant that he was refusing chest compressions or other life-sustaining measures, should his heart stop beating. I was utterly stunned when I saw David’s signature on the bottom of his DNR sheet. In nursing homes, it is uncommon to see an individual sign this order themselves. Perhaps this is because most people in nursing homes are in their eighties and nineties. Never before in history have people lived this long. Nor have we had the technology to keep people alive as long as we can today. These days, what many workers in nursing homes often witness are patients with terminal illnesses and advanced dementia being kept alive. This is accomplished with feeding tubes, which supply artificial nutrition to patients when they can no longer eat. A plastic device is implanted in the stomach and nutrient-rich liquid is delivered directly to the stomach to keep someone alive. This is called a G tube. Most DNR’s of the elderly are signed by their next of kin. People of advanced age have not been educated on what artificial nutrition actually means or how it will impact their lives. By the time one of these patients would require a feeding tube, he or she is often confused and unable to sign any such form or make this type of decision. Somehow, this 34 year old man named David, born in the Dominican Republic, had been clever and spiritually aware enough to acknowledge that this would not be the picture of his end of life story. David would not be kept alive on a feeding tube. He was brave in a way that I had never seen before. There was bold intent in his signature on the bottom of his DNR form. David was going to die well, and on his own terms. David was released from the nursing home. A year went by. And then, like the flutter of a hummingbird’s wing, I heard from him again via email. David had met a woman named Marija. She lived in Finland, but had been flying into the Newark Liberty Airport to see him. David and Marija had fallen in love.

As David and Marija’s romance progressed, David did the unthinkable. He rescinded his DNR. He went to a local hospital and had a G tube implanted. (The G is for Gangsta, David said). I remember hearing of this and rescinding my own ideas about feeding tubes. I had previously believed them to fall into the category of cruel to the elderly with dementia. But as David was of sound mind, able to make his own decisions and newly in love, I was overjoyed. He wanted to stay alive for Marija. This was David’s fearless new step. He did not want to die. Christmas is important to many people, in many cultures, for many various reasons. I knew that for Marija, Christmas was usually cold and snow covered the ground in her town, just outside Helsinki. Due to climate changes, Marija said that when it did not snow, the locals referred to this as a ‘Black Christmas’. The people of Finland got very upset when they had Black Christmases. As for David, his family usually cooked pernil (pig) and green plantains. His mother and younger brothers relied on him to create the feast, drive them to a local midnight mass, and buy and wrap presents to ensure a wondrous holiday. Throughout the entire day of Christmas in the year 2015, Marija prepared fish roe and herring, rutabaga casserole and rice porridge (the porridge was her favorite thing). She wrapped presents for her children. She called David from Finland and sent him pictures and videos of her kids. Marija was delighted that snow was falling during her daily jog. In New Jersey, David lay on the couch in his mother’s sala (Spanish for living room), as he smelled the pig from the oven and watched his family dance to music. He was too weak to get to Christmas mass, but strong enough to sit up for a few minutes and watch his brothers open presents. It was on the very next morning, the day after Christmas, when David’s heart stopped beating. I remember working in the very same nursing home where I met him, passing the room where he stayed, when I heard the news. I reached out to Marija. It was a horrible day, a day that seemed to last far too long, a day when we wished we could fall asleep at noon and hope that this had been something that was not true.

As the years have worn on, we have a different perspective. I still talk to Marija in Scandinavia. It is David’s true love, the one for whom he finally agreed on a feeding tube, who helps me to see the victory in David’s death. “David did not want me to have a Black Christmas,” Marija tells me. “He chose to wait until the day after Christmas to leave.”

These are the words that I needed. I did not know David all that well. But when I think of David’s family, I can imagine the sounds of their voices around the Christmas tree. I can smell the ham roasting in the oven. This smell of food must have brought up a round of nausea within David’s throat, due to his chemotherapy during that time. He could not eat at all towards the end. But he did not allow himself to lie down completely, he willed himself to keep breathing for that entire day, so that his family would have a good Christmas. Like Saint Ignatius, David was sent many sufferings. He suffered so beautifully, so quietly, without a complaint or concern for himself. Rather, David worried about all of us. That is why he chose to spare his people such a great loss on Christmas Day. David chose to die on the day after Christmas. I sometimes go to his grave and try to talk to him. I ask him how he could have endured the length of time he spent on this planet, in pain, without teeth, with so many people to worry about, and with the knowledge that he was going to die so young. I know what he would say, as I stand on the frozen ground where he is buried: Have a Merry Christmas. Do not think for a second that God is not with us, in every moment. Tell my girl that I love her. As the world prepares for the lighting of the first Hanukkah candle, I am reminded of one of my fondest relationships. I once had a Jewish husband. We were married for roughly three years. His name was Benny and he was very old. I met Benny when he was 92. At that time, I was in my late thirties. Benny had panache. At age 92, he made advances towards every single woman in the nursing home. Most of them turned away from him in disgust. But there was something about this man that appealed to me. He was undaunted by rejection. His flair in speaking and hand gesticulations were evidence of a man who had really been somebody before dementia had set in. “Darling, you are so beautiful,” Benny declared to every woman who crossed his path. “Do you want to marry me?" Each morning, Benny sat in the foyer of the nursing home, right at the entry. When our relationship first heated up, this guy read The New York Times. By the end, he could not read or follow what was happening on the news. That never really mattered to me. What mattered was Benny’s interest in people. He loved socializing, he loved politics. I wondered how he had come to be this ebullient person. I learned about Benny’s past by talking to his children and other residents of the nursing home. Benny was conceived in Siberia, in the year 1919. His mother’s name was Rachel. This pregnancy of Rachel’s fell at the same time in Russia when Jewish people were being murdered by the Bolsheviks in pograms. Rachel discovered that she was pregnant with her first child and fled across the continent. She gave birth to Benny in a snowy field, and a local farmgirl came to assist her in the delivery. Through a series of miraculous events, Rachel, her husband and their son Benny traveled through Eastern Europe and wound up on a boat headed to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Benny had no more than a sixth-grade education. While I never knew Benny’s father’s name, I learned that he had a respiratory disorder. So, what did Benny do, as a Russian 12-year old immigrant child? He worked in a factory to support his parents and his younger siblings.

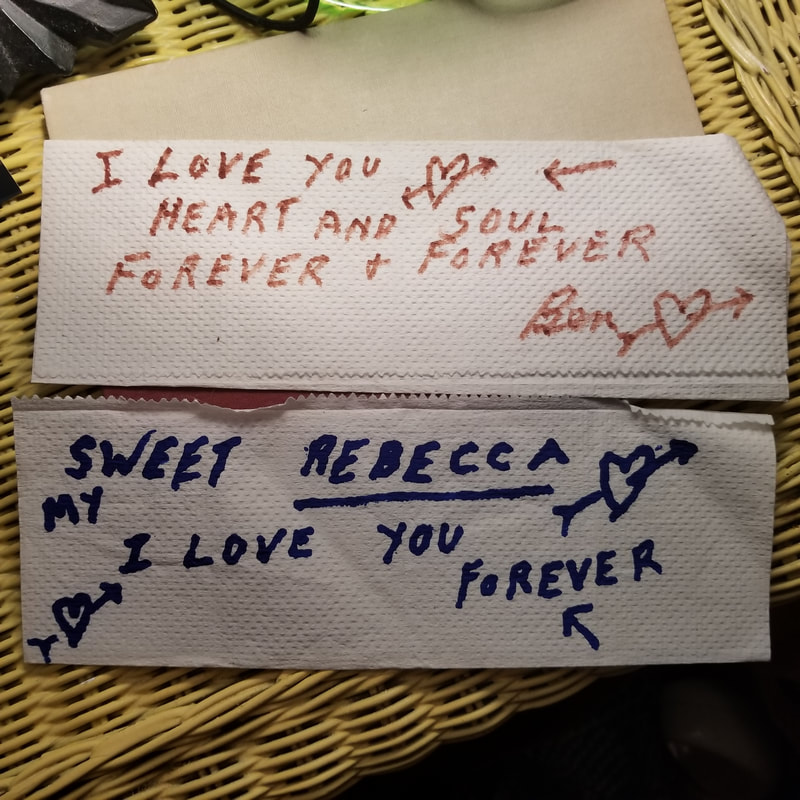

But again, how did I come to be wed to this old man, you may be wondering? Benny liked that I had a Jewish name. He began writing love letters on paper towels and left them near my computer desk. He started to tell all the staff and residents that I was going to become his wife. My coworkers rolled their eyes. His fellow residents scoffed at him. The more the others found our companionship to be ridiculous, the more I returned Benny’s affections. I took to greeting him with relish and never denied his marriage proposals. A few months later, Benny sat with The New York Timeswrapped on his lap in his wheelchair in the foyer of the nursing home. He asked why his wife was late for work (even in his confusion he had figured out that I am a late sleeper), and the staff began to play along with the delusion of our marriage. The cooking staff asked me to watch my husband eat, to ensure he was getting enough nutrition. The nurse’s aides asked me if I could help to pick out Benny’s clothes, because he refused to wear anything without his wife’s approval. The hairdresser implored, “Can you please bring your husband to the beauty salon today? He needs a haircut and will not listen to me.” Through the three years of this delusional relationship, I tried to uncover all that I could about Benny. I spoke with his son Jeffrey, a broad-shouldered and bearded ex-hippie. Jeffrey visited the nursing home quite a bit. He was the person who explained Benny’s Jewish faith. “My Dad was involved in the Massah and Aliyah movements in the late 1940’s. These were the revolutionary groups who helped to found Zionism. My father stood on the corners of Greenwich Village and shouted to anyone who would listen about the necessity of the State of Israel for the Jews after World War II. He was a fiercely political man.” I was spellbound. Jeffrey showed me pictures of his father Benny and his mother Sylvia meeting dignitaries by the Dead Sea in the late 1960’s. They had been tucked away in Benny’s sock drawer. “My father always wanted to move to Israel, but my mother forbade it,” Jeffrey told me. “I think that always tore at my Dad. His soul was living in Jerusalem, but the rest of his body was forced to live in Brooklyn, New York.” As Jeffrey and I spoke of these things, Benny ate egg drop soup (his favorite), and gazed at the two of us adoringly. My husband would stop and ask his son, “Do you think I should marry Rebecca?” Jeffrey always replied, “Yes, Dad. I think Mom would approve of this girl for you.” I guess you could say that our marriage was ephemeral. It felt like a dream. An odd dream, as Benny would show up at the rehab gym each morning and ask where his wife was. My coworkers would tell him that his wife began working at 10:30 and that I would show up later. Benny became an everyday presence in my working life, and I knelt to hug and kiss him in his wheelchair each morning. Much as one would a spouse. Benny’s son Jeffrey had a daughter who was getting married. It was important to Jeffrey that Benny attended his grand-daughter’s wedding. But Jeffrey also knew that Benny did little without me. I was invited to a large and beautiful event in August with Benny as my date. I had gotten a spray-tan and a fancy updo so that I looked as elegant as Benny in his suit. As we entered the venue, and I pushed him in his wheelchair, I was not blind to all the snickering and nudging of the other wedding attendants. While I cut up Benny’s steak that evening, it was clear what everybody was thinking. They believed I was some sort of Anna Nicole Smith, who was after Benny’s money. The truth was that Benny had no money. Jeffrey had filed a Medicaid application for his father years ago. Benny had a great time that night, however. He danced in his wheelchair to the Hava Nagila. He became confused at times and asked where we were. I simply reached for his hand and he resumed smiling and laughing.

There were afternoons when he would be sitting in the Day Room and suddenly place his forehead on the table in front of him. Benny could be heard shouting: “I am dying! Someone please help me! I cannot even pick my head up off this table! Please help me!” Ten minutes later, Benny would promptly sit up and wheel himself back to his bedroom. (These were the moments when I giggled uncontrollably; I wept with laughter and tears of mirth fell down my cheeks. Benny’s theatrical flair and determination to get the attention he deserved were what I loved most about him. Yet all the while, I knew what was coming. Benny would leave us soon).

When the last few weeks of his death were approaching, Benny no longer wheeled himself around. He no longer looked for his wife. Instead, I sat next to him and held his hand. For a short man, he had enormous hands. He looked up at me and said, “I love you, Rebecca-la. I am so glad we got married.” Benny kept lingering. His family began to take vigil in Benny’s room and I was reluctant to go inside. While his family was grateful for the succor I had given their father and grandfather in his later years, it was most embarrassing when Benny’s eyes flew open when I entered the room and he stated, “Here she is! I love her!” I stayed away from that entire hallway of the nursing home during those days. Each night I went home and wondered why Benny was still alive. What was he hanging on for, exactly? But he kept on living, and his children and grandchildren sat around him in a watchful throng. It was not until February 29th, leap year day, the day that only happens every four years, when Benny drew his last breath. It was true that everything about Benny’s life was remarkable. He had been born under great peril in a snowy field in Siberia. He had fought without tiring for the establishment of Israel as a haven for Jewish people after the war. Benny was a man who had controlled his environment as best as he could. Despite the many obstacles in his path, Benny had great willpower. He had worked since the sixth grade to support his family of origin, he had opened a dry-cleaning business in adulthood to ensure the well-being of his wife and kids, and he had traveled to Israel several times to see the land he had helped to secure for his fellow Jewish people. In his last years, Benny wed a much younger woman. While most people dwindle and weaken like brown flowers without water in a nursing home, Benny had thrived. I went to Benny’s funeral. I heard his son Jeffrey speak about Benny’s views on religion: “Man created God, not the other way around.” Benny had not been a believer in the spiritual aspect of Judaism, even though he went to Temple and celebrated all the Jewish holidays. No, Benny was a believer in fighting for his heritage. He fought for his roots in Russia, when Bolsheviks were attempting to kill his people. He fought for Israel, for Zionism. There were many days when I drove home from working in that nursing home and I felt more secure about the world. This was because of Benny. Benny did not espouse the idea of miracles or God’s direction for our lives. Rather, he believed in the individual’s ability to alter the world through his or her own will, intellect, politics, actions and fighting for the good. It seemed to be no mistake that Benny willed his own death on the most remarkable day on the calendar, February 29th. I know that Benny decided on the moment of his own death. His son Jeffrey knew it also. I was thrilled to see Jeffrey a few weeks after Benny’s death, when he dropped off sandwiches for the staff in thanks for all they had done. “Just so you know, everyone knows it was you who kept my father alive for the last three years. You did a great job as his wife. You also made one hell of a step-mother…" I believe that I was a good wife to Benny, in our bizarre and complicated romance. But I do not think that I kept Benny alive for as long as he lived. If anything, I believe the opposite to be true. I was working in one of the hardest environments possible. I wept frequently, could not sleep many nights and felt purposeless in performing my job duties at the nursing home. It had been this short Jewish guy who greeted me at the sliding glass doors each morning who helped me to keep living. He showed me that we cannot always look for miracles; we must look for ways where we can summon the strength in our souls to create a world that we want to see, for ourselves and those that we love. I will light a candle for Hanukkah this year. I will light it for my Jewish husband, even though he would find that unnecessary. Maybe I should get one of those old-fashioned matchboxes, the kind with the very sturdy sticks. Yes, I will quickly strike the colored tip of the wooden match along the phosphorus surface of the box and watch the flame suddenly come to life. I will listen for the electrical crackle that happens in that instant. I won’t await a miracle. Instead, I will act and fight and choose my life and my (hopefully distant) death as well as I possibly can. Just as my Jewish husband did. |

Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|